Rendering Pattern

Progressive Hydration

A server rendered application uses the server to generate the HTML for the current navigation. Once the server has completed generating the HTML contents, which also contains the necessary CSS and JSON data to display the static UI correctly, it sends the data down to the client. Since the server generated the markup for us, the client can quickly parse this and display it on the screen, which produces a fast First Contentful Paint!

Although server rendering provides a faster First Contentful Paint, it doesn’t always provide a faster Time To Interactive. The necessary JavaScript in order to be able to interact with our website hasn’t been loaded yet. Buttons may look interactive, but they aren’t interactive (yet). The handlers will only get attached once the JavaScript bundle has been loaded and processed. This process is called hydration: React checks the current DOM nodes, and hydrates the nodes with the corresponding JavaScript.

The time that the user sees non-interactive UI on the screen is also refered to as the uncanny valley: although users may think that they can interact with the website, there are no handlers attached to the components yet. This can be a frustrating experience for the user, as the UI may look like it’s frozen!

It can take a while before the DOM components that were received from the server are fully hydrated. Before the components can be hydrated, the JavaScript file needs to be loaded, processed, and executed. Instead of hydrating the entire application at once, like we did previously, we can also progressively hydrate the DOM nodes. Progressive hydration makes it possible to individually hydrate nodes over time, which makes it possible to only request the minimum necessary JavaScript.

By progressively hydrating the application, we can delay the hydration of less important parts of the page. This way, we can reduce the amount of JavaScript we have to request in order to make the page interactive, and only hydrate the nodes once the user needs it. Progressive hydration also helps avoid the most common SSR Rehydration pitfalls where a server-rendered DOM tree gets destroyed and then immediately rebuilt.

Progressive hydration allows us to only hydrate components based on a certain condition, for example when a component is visible in the viewport. In the following example, we have a list of users that gets progressively hydrated once the list is in the viewport. The purple flash shows when the component has been hydrated!

1import React from "react";2import { hydrate } from "react-dom";3import App from "./components/App";45hydrate(<App />, document.getElementById("root"));

Although it happens fast, you can see that the initial UI is the same as the UI in its hydrated state! Since the initial HTML contained the same information and styles, we can seamlessly make the components interactive without any flashy or jumpy UI. Progressive hydration makes it possible to conditionally make certain components interactive, while this can go completely unnoticed to your app’s users.

Progressive Hydration Implementation

In the section on implementing SSR with React, we discussed client-side hydration for an app that is rendered on the server. Hydration allows client-side React to recognize the ReactDOM components that are rendered on the server and attach events to these components. Thus, it introduces continuity and seamlessness for an SSR app to function like a CSR app once it is available on the client.

For all components on the page to become interactive via hydration, the React code for these components should be included in the bundle that gets downloaded to the client. Highly interactive SPAs that are largely controlled by JavaScript would need the entire bundle at once. However, mostly static websites with a few interactive elements on the screen, may not need all components to be active immediately. For such websites sending a huge React bundle for each component on the screen becomes an overhead.

Progressive Hydration solves this problem by allowing us to hydrate only certain parts of the application when the page loads. The other parts are hydrated progressively as required.

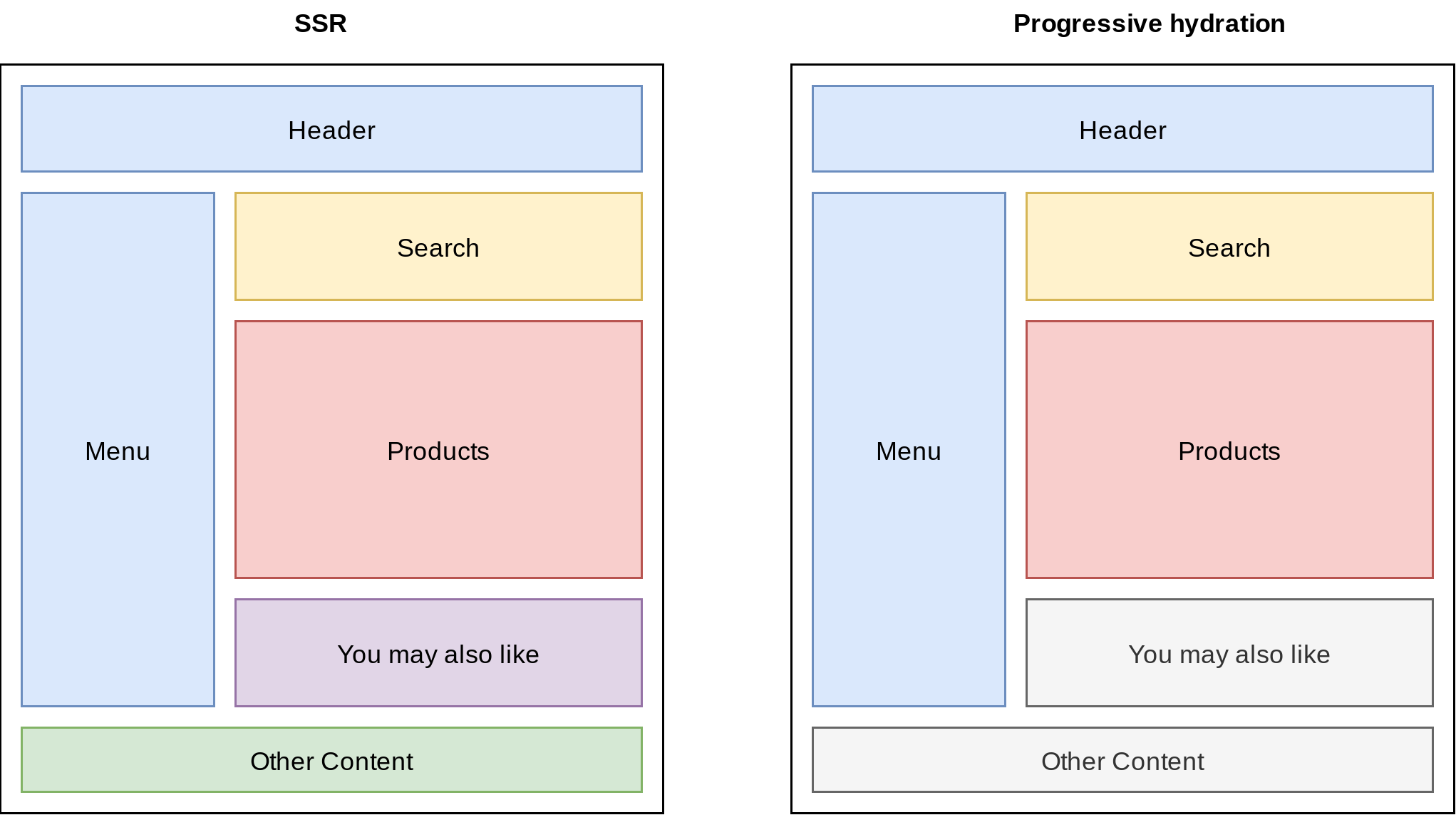

With Progressive hydration, the “You may also like” and “Other content” components can be hydrated later.

Instead of initializing the entire application at once, the hydration step begins at the root of the DOM tree, but the individual pieces of the server-rendered application are activated over a period of time. The hydration process may be arrested for various branches and resumed later when they enter the viewport or based on some other trigger. Note that, the loading of resources required to perform each hydration is also deferred using code-splitting techniques, thereby reducing the amount of JavaScript required to make pages interactive.

The idea behind progressive hydration is to provide a great performance by activating your app in chunks. Any progressive hydration solution should also take into account how it will impact the overall user experience. You cannot have chunks of screen popping up one after the other but blocking any activity or user input on the chunks that have already loaded. Thus, the requirements for a holistic progressive hydration implementation are as follows.

- Allows usage of SSR for all components.

- Supports splitting of code into individual components or chunks.

- Supports client side hydration of these chunks in a developer defined sequence.

- Does not block user input on chunks that are already hydrated.

- Allows usage of some sort of a loading indicator for chunks with deferred hydration.

React concurrent mode will address all these requirements once it is available to all. It allows React to work on different tasks at the same time and switch between them based on the given priority. When switching, a partially rendered tree need not be committed, so that the rendering task can continue once React switches back to the same task.

Concurrent mode can be used to implement progressive hydration. In this case, hydration of each of the chunks on the page, becomes a task for React concurrent mode. If a task of higher priority like user input needs to be performed, React will pause the hydration task and switch to accepting the user input. Features like lazy(), Suspense() allow you to use declarative loading states. These can be used to show the loading indicator while chunks are being lazy loaded. SuspenseList() can be used to define the priority for lazy loading components.This demo shared by Dan Abramov shows concurrent mode in action and implements progressive hydration.

React concurrent mode can also be combined with another React feature

- Server Components. This will allow you to refetch components from the server and render them on the client as they stream in instead of waiting for the whole fetch to finish. Thus, the client’s CPU is put to work even as we wait for the network fetch to finish.

While the React concurrent mode based progressive hydration implementation is still getting ready, many other contenders for a partial hydration implementation are available. Progressive hydration was demonstrated at Google I/O ‘19. The demo for progressive hydration showed the use of a Hydrator component to hydrate selected sections of the page. Multiple implementations have spawned from this for different client-side frameworks. Implementations are also available for Vue, Angular and Next.js.

Let is take a quick look at one such method using Preact and Next.js

This is a POC for partial hydration using

pool-attendant-preact:A library that implements partial hydration with preact x.next-super-performance:A Next.js plugin that uses this library to improve client-side performance.

The pool-attendant-preact library includes an API called withHydration which

lets you mark your more interactive components for hydration. These will be

hydrated first. You can use this to define your page content as follows.

import Teaser from "./teaser";

import { withHydration } from "next-super-performance";

const HydratedTeaser = withHydration(Teaser);

export default function Body() {

return (

<main>

<Teaser column={1} />

<HydratedTeaser column={2} />

<HydratedTeaser column={3} />

<Teaser column={1} />

<Teaser column={2} />

<Teaser column={3} />

<Teaser column={1} />

<Teaser column={2} />

<Teaser column={3} />

</main>

);

}The component HydratedTeaser in columns 2 and 3 will be hydrated first. You

can now hydrate the remaining components on the client using the hydrate() API

which is also included in the library.

import { hydrate } from "next-super-performance";

import Teaser from "./components/teaser";

hydrate([Teaser]);The component HydrationData is used to write serialized props to the client.

It will ensure that the required props are available to the components being

hydrated.

import Header from "../../components/header";

import Main from "../../components/main";

import { HydrationData } from "next-super-performance";

export default function Home() {

return (

<section>

<Header />

<Main />

<HydrationData />

</section>

);

}Pros and Cons

Progressive hydration provides server-side rendering with client-side hydration while also minimizing the cost of hydration. Following are some of the advantages that can be gained from this.

-

Promotes code-splitting: Code-splitting is an integral part of progressive hydration because chunks of code need to be created for individual components that are lazy- loaded.

-

Allows on-demand loading for infrequently used parts of the page: There may be components of the page that are mostly static, out of the viewport and/or not required very often. Such components are ideal candidates for lazy loading. Hydration code for these components need not be sent when the page loads. Instead, they may be hydrated based on a trigger.

-

Reduces bundle size: Code-splitting automatically results in a reduction of bundle size. Less code to execute on load helps reduce the time between FCP and TTI.

Note (React 18+): Use

<Suspense>withlazy()for Hydration ControlReact 18’s Concurrent Features now address the progressive hydration requirements: selective hydration on interaction means if the user tries to interact with a not-yet-hydrated part, React will prioritize hydrating that part—this is built-in.

A practical pattern is to wrap non-critical components in a

<Suspense fallback={...}>. On the server, render a lightweight placeholder, and code-split the real component withReact.lazy. For example:const Comments = React.lazy(() => import('./Comments')); // ... <Suspense fallback={null}> <Comments {...props} /> </Suspense>This streams a placeholder in the SSR output and doesn’t block the rest of the page. The

Commentscomponent hydrates once its code is fetched. In Next.js, usenext/dynamicwith{ ssr: false }for truly client-only widgets, or Suspense for parts that can be temporarily left as loading. The key is to make the user perceive the app as interactive as soon as possible, even if under the hood some parts activate slightly later.

On the downside, progressive hydration may not be suitable for dynamic apps where every element on the screen is available to the user and needs to be made interactive on load. This is because, if developers do not know where the user is likely to click first, they may not be able to identify which components to hydrate first.