Performance Pattern

Compressing JavaScript

Compress your JavaScript and keep an eye on your chunk sizes for optimal performance. Overly high JavaScript bundle granularity can help with deduplication & caching, but can suffer from poorer compression & impact loading in the 50-100 chunks range (due to browser processes, cache checks etc). Ultimately, pick the compression strategy that works best for you.

JavaScript is the second biggest contributor to page size and the second most requested web resource on the internet after images. We use patterns that reduce the transfer, load, and execution time for JavaScript to improve website performance. Compression can help reduce the time needed to transfer scripts over the network.

You can combine compression with other techniques such as minification, code-splitting, bundling, caching, and lazy-loading to reduce the performance impact of large amounts of JavaScript. However, the goals of these techniques can sometimes be at odds with each other. This section explores JavaScript compression techniques and discusses the nuances you should consider when deciding on a code-splitting and compression strategy.

- Gzip and Brotli are the most common ways to compress JavaScript and are widely supported by modern browsers.

- Brotli offers a better compression ratio at similar compression levels.

- Next.js provides Gzip compression by default but recommends enabling it on an HTTP proxy like Nginx.

- If you use Webpack to bundle your code, you can use the CompressionPlugin for Gzip compression or the BrotliWebpackPlugin for Brotli compression.

- Oyo saw a 15-20% reduction, and Wix saw a 21-25% reduction in file sizes after switching to Brotli compression instead of Gzip.

- compress(a + b) <= compress(a) + compress(b) - A single large bundle will give better compression than multiple smaller ones. This causes the granularity trade-off where ** De-duplication and caching are at odds with browser performance and compression. Granular chunking ** can help deal with this trade-off.

HTTP compression

Compression reduces the size of documents and files, so they take up less disk space than the originals. Smaller documents consume lower bandwidth and can be transferred over a network quickly. HTTP compression uses this simple concept to compress website content, reduce page weights, lower bandwidth requirement, and improve performance.

HTTP data compression may be categorized in different ways. One of them is lossy vs. lossless.

Lossy compression implies that the compression-decompression cycle results in a slightly altered document while retaining its usability. The change is mostly imperceptible to the end-user. The most common example of lossy compression is JPEG compression for images.

With Lossless compression, the data recovered after compression and subsequent decompression will match precisely with the original. PNG images are an example of lossless compression. Lossless compression is relevant to text transfers and should be applied to text-based formats such as HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

Since you want all valid JS code on the browser, you should use lossless compression algorithms for JavaScript code. Before we compress the JS, minification helps eliminate the unnecessary syntax and reduce it to only the code required for execution.

Minification

To reduce payload sizes, you can minify JavaScript before compression. Minification complements compression by removing whitespace and any unnecessary code to create a smaller but perfectly valid code file. When writing code, we use line breaks, indentation, spaces, well-named variables, and comments to improve code readability and maintainability. However, these elements contribute to the overall JavaScript size and are not necessary for execution on the browser. Minification reduces the JavaScript code to the minimum required for successful execution.

Minification is a standard practice for JS and CSS optimization. It’s common for JavaScript library developers to provide minified versions of their files for production deployments, usually denoted with a min.js name extension. (e.g., jquery.js and jquery.min.js)

Multiple tools are available for the minification of HTML, CSS, and JS resources. Terser is a popular JavaScript compression tool for ES6+, and Webpack v4 includes a plugin for this library by default to create minified build files. You can also use the TerserWebpackPlugin with older versions of Webpack or use Terser as a CLI tool without a module bundler.

Static vs. dynamic compression

Minification helps to reduce file sizes significantly, but compression of JS can provide more significant gains. You can implement server-side compression in two ways.

Static Compression: You can use static compression to pre-compress resources and save them ahead of time as part of the build process. You can afford to use higher compression levels, in this case, to improve the download time for code. The high build-time will not affect the website performance. It would be best if you used static compression for files that do not change very often.

Dynamic Compression: With this process, compression takes place on the fly when the browser requests resources. Dynamic compression is easier to implement, but you are restricted to using lower compression levels. Higher compression levels would require more time, and you would lose the advantage gained from the smaller content sizes. It would help if you used dynamic compression with content that changes frequently or is application-generated.

You can use static or dynamic compression depending on the type of application content. You can enable both static and dynamic compression using popular compression algorithms, but the recommended compression levels are different in each case. Let us look at compression algorithms to understand this better.

Compression algorithms

Gzip and Brotli are the two most common algorithms used for compressing HTTP data today.

Gzip

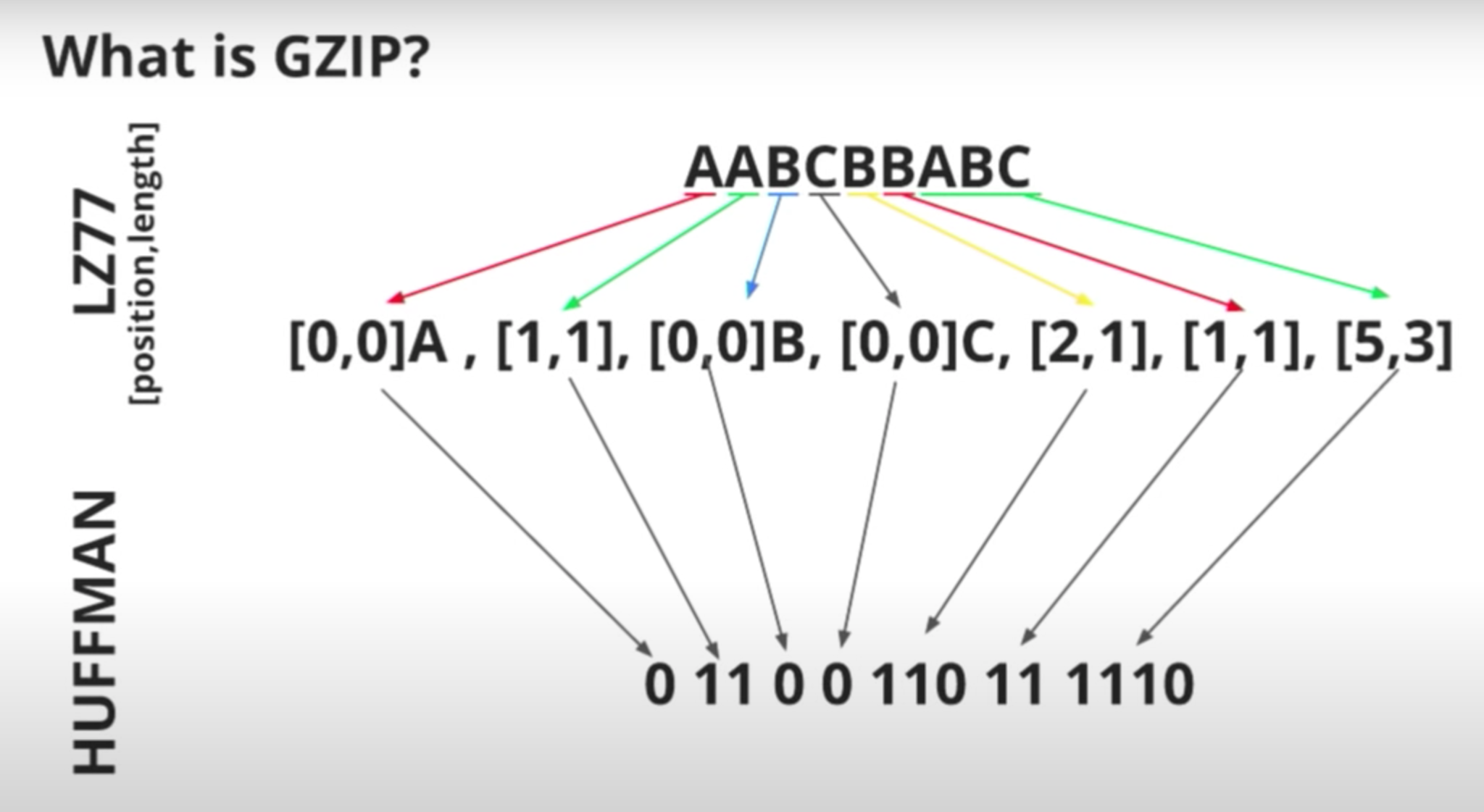

The Gzip compression format has been around for almost 30 years and is a lossless algorithm based on the Deflate algorithm. The deflate algorithm itself uses a combination of the LZ77 algorithm and Huffman coding on blocks of data in an input data stream.

The LZ77 algorithm identifies duplicate strings and replaces them with a backreference, which is a pointer to the place where it previously appeared, followed by the length of the string. Subsequently, Huffman coding identifies the commonly used references and replaces them with references with shorter bit sequences. Longer bit sequences are used to represent infrequently used references.

Image Courtesy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whGwm0Lky2s&t=851s

All major browsers support Gzip. The Zopfli compression algorithm is a slower but improved version of Deflate/Gzip, producing smaller GZip compatible files. It is most suitable for static compression, where it can provide more significant gains.

Brotli

In 2015, Google introduced the Brotli algorithm and the Brotli compressed data format. Like GZip, Brotli too is a lossless algorithm based on the LZ77 algorithm and Huffman coding. Additionally, it uses 2nd order context modeling to yield denser compression at similar speeds. Context modeling is a feature that allows multiple Huffman trees for the same alphabet in the same block. Brotli also supports a larger window size for backreferences and has a static dictionary. These features help increase its efficiency as a compression algorithm.

Brotli is supported by all major servers and browsers today and is becoming increasingly popular. It is also supported and can be easily enabled by hosting providers and middleware including Netlify, AWS and Vercel.

Websites with a large user base, such as OYO and Wix, have improved their performance considerably after replacing Gzip with Brotli.

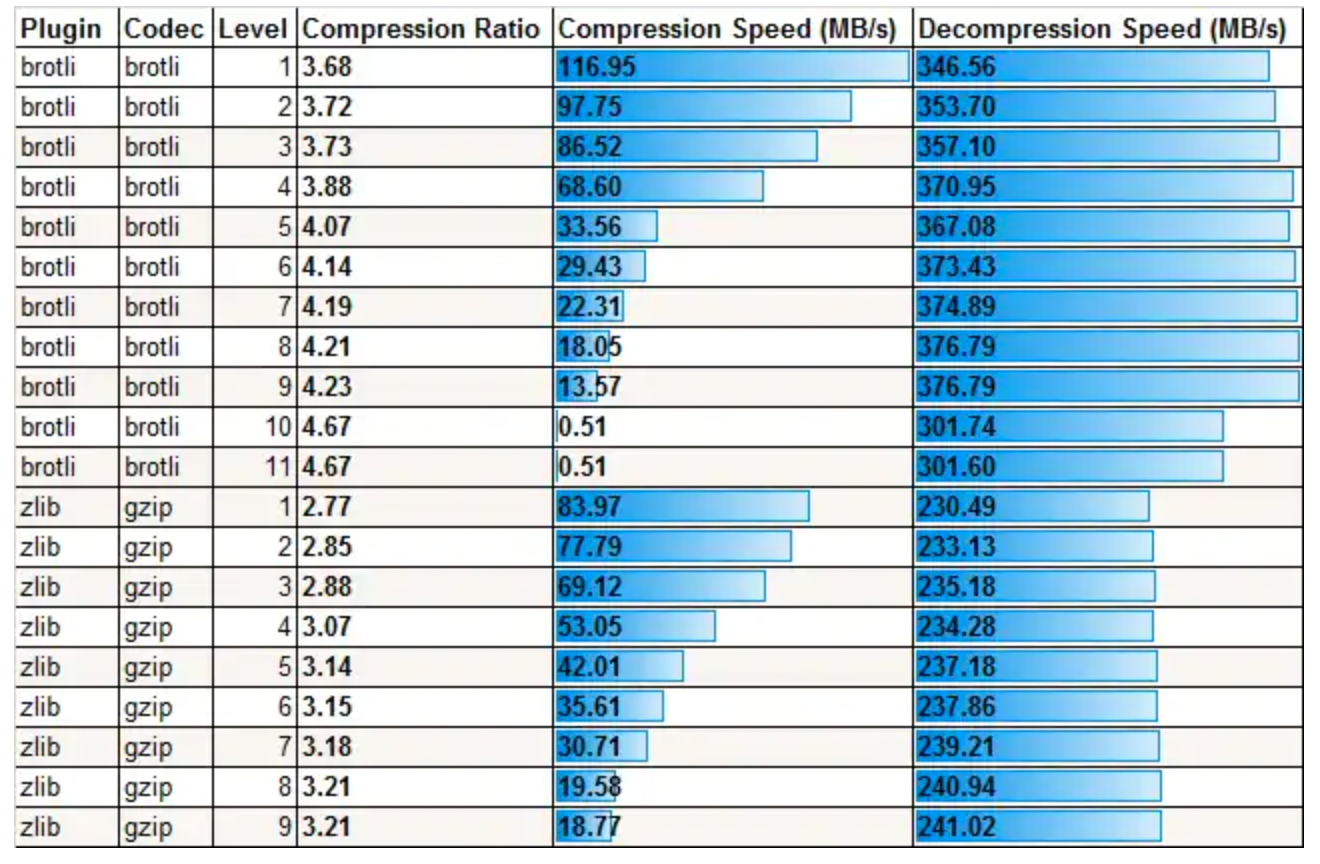

Comparing Gzip and Brotli

The following table shows a benchmark comparison of Brotli and Gzip compression ratios and speeds at different compression levels.

Additionally, here are a few insights from Chrome research into compression of JS using Gzip and Brotli

- Gzip 9 has the best compression rate with a good compression speed, and you should consider using it before other levels of Gzip.

- With Brotli, consider levels 6-11. Otherwise, we can achieve a similar compression rate much faster with Gzip.

- Over all size ranges Brotli 9-11 performs much better than Gzip, but it’s pretty slow.

- The bigger the bundle, the better compression rate and speed you would get.

- The relationships between algorithms are similar for all bundle sizes (for example, Brotli 7 is better than Gzip 9 for every bundle size, and Gzip 9 is faster than Brotli 5 for all size ranges).

Let us now take a look at the communication about chosen compression format between servers and browsers.

Enabling compression

You can enable static compression as part of the build. If you use Webpack to bundle your code, you can use the CompressionPlugin for Gzip compression or the BrotliWebpackPlugin for Brotli compression. The plugin can be included in the Webpack config file as follows.

module.exports = {

//...

plugins: [

//...

new CompressionPlugin(),

],

};Next.js provides Gzip compression by default but recommends enabling it on an HTTP proxy like Nginx. Both Gzip and Brotli are supported on the Vercel platform at the proxy level.

You can enable dynamic lossless compression on servers (including Node.js) that support different compression algorithms. The browser communicates the compression algorithms it supports through the Accept-Encoding HTTP header in the request. For example, Accept-Encoding: gzip, br.

This indicates that the browser supports Gzip and Brotli. You can enable different types of compression on your server by following instructions for the specific server type. For example, you can find instructions for enabling Brotli on the Apache server here. Express is a popular web framework for Node and provides a compression middleware library. Use it to compress any asset as it gets requested.

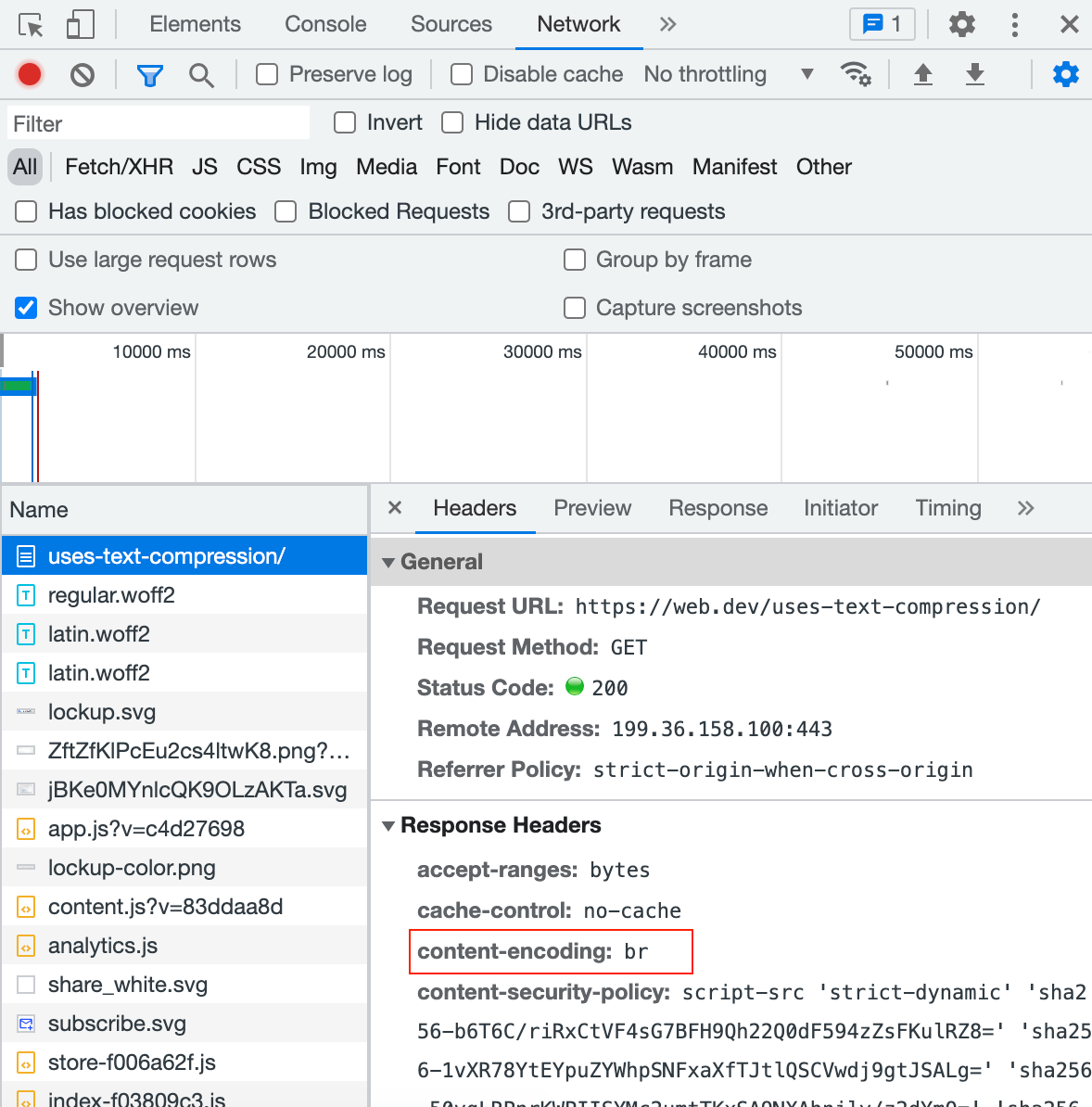

Brotli is recommended over other compression algorithms because it generates smaller file sizes. You can enable Gzip as a fallback for browsers that don’t support Brotli. If successfully configured, the server will return the Content-Encoding HTTP response header to indicate the compression algorithm used in the response. E.g., Content-Encoding: br.

Auditing compression

You can check if the server compressed the downloaded scripts or text in Chrome -> DevTools -> network -> Headers. DevTools displays the content-encoding used in the response, as shown below.

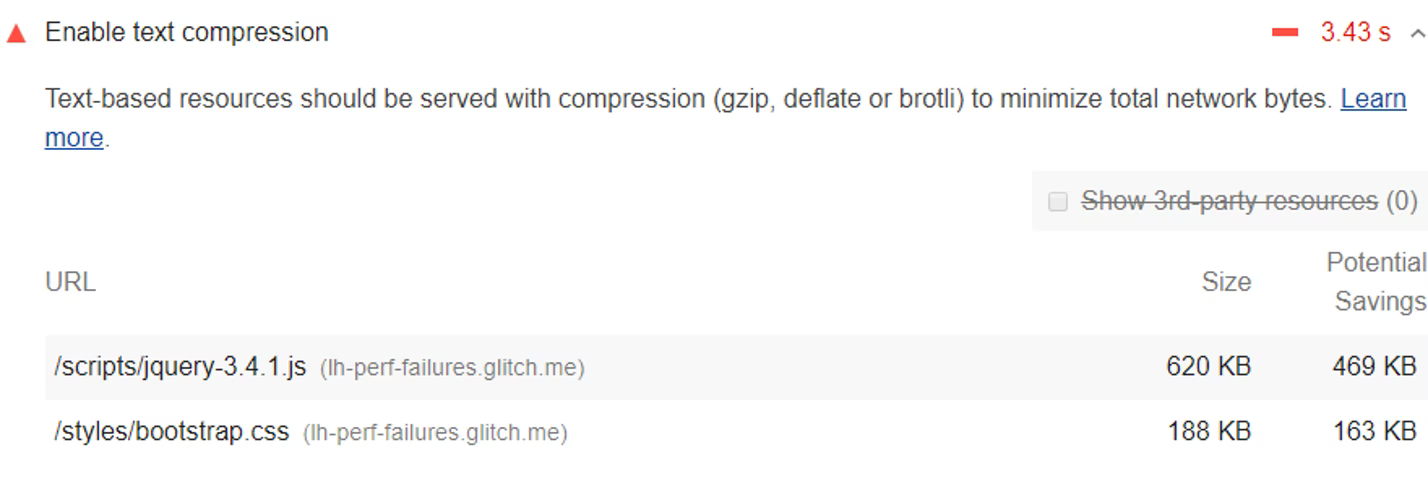

The lighthouse report includes a performance audit for “Enable Text Compression” that checks for text-based resource types received without the content-encoding header set to ‘br’, ‘gzip’ or ‘deflate’. Lighthouse uses Gzip to compute the potential savings for the resource.

Image courtesy: https://web.dev/uses-text-compression/#how-to-enable-text-compression-on-your-server

JavaScript compression and loading granularity

To fully grasp the effects of JavaScript compression, you must also consider other aspects of JavaScript optimization, such as route-based splitting, code-splitting, and bundling.

Modern web applications with large amounts of JavaScript code often use different code-splitting and bundling techniques to load code efficiently. Apps use logical boundaries to split the code, such as route level splitting for Single Page Applications or incrementally serving JavaScript on interaction or viewport visibility. You can configure bundlers to recognize these boundaries.

Let us cover some basic definitions related to code-splitting and bundling before we proceed to how this affects compression.

Bundling terminology

Following are some of the key terms relevant to our discussion.

- Module: Modules are discrete chunks of functionality designed to provide solid abstractions and encapsulation. See Module pattern for more detail.

- Bundle: Group of distinct modules that contain the final versions of source files and have already undergone the loading and compilation process in the bundler.

- Bundle splitting: The process utilized by bundlers to split the application into multiple bundles such that each bundle can be isolated, published, downloaded, or cached independently.

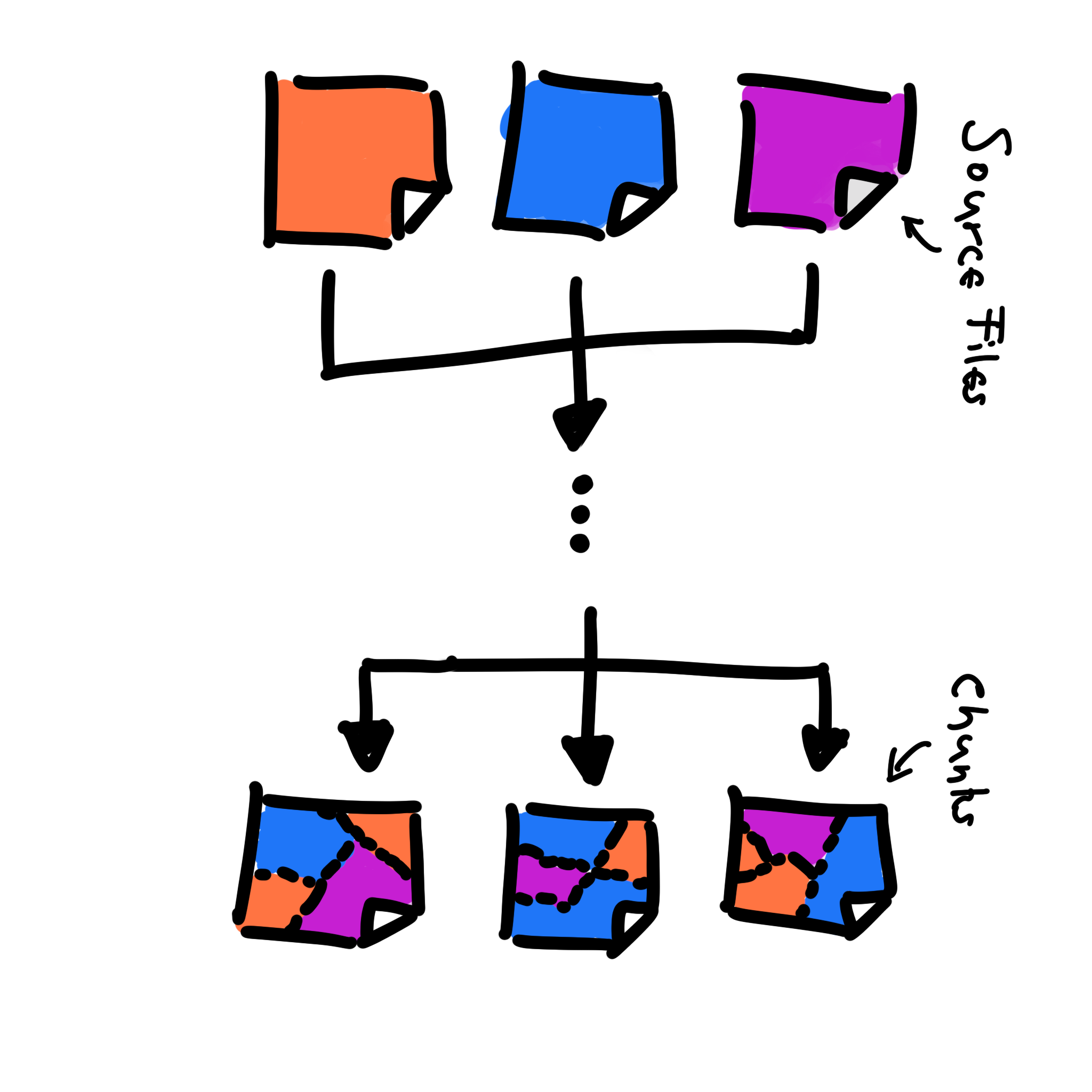

- Chunk: Adopted from Webpack terminology, a chunk is the final output of the bundling and code-splitting process. Webpack can split bundles into chunks based on the entry configuration, SplitChunksPlugin, or dynamic imports.

If modules are contained in source files, then the final output of the build process after code or bundle splitting is known as a chunk. Note that both the source files and the chunks may be dependent on each other.

Image courtesy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ImjzA7EMI6I&list=PLyspMSh4XhLP-mqulUMcaqTbLo-ZJxSX5&index=29

The output size for JavaScript refers to the size of chunks or raw size after optimization by a JavaScript bundler or compiler. Large JS applications can be deconstructed into chunks of independently loadable JavaScript files. Loading granularity refers to the number of output chunks—the higher the number of chunks, the smaller each chunk’s size and higher the granularity.

Some chunks are more critical than others because they are loaded more frequently or are part of more impactful code paths (e.g., loading the ‘checkout’ widget). Knowing which chunks matter most requires application knowledge, though it is safe to assume that the ‘base’ chunk is always essential.

Every byte of the chunks required by a page needs to be downloaded and parsed/executed by user devices. This is the code that directly affects the application performance. Since chunks are the code that will be eventually downloaded, compressing chunks can lead to better download speeds.

With that background, let us discuss the interplay between loading granularity and compression.

The granularity trade-off

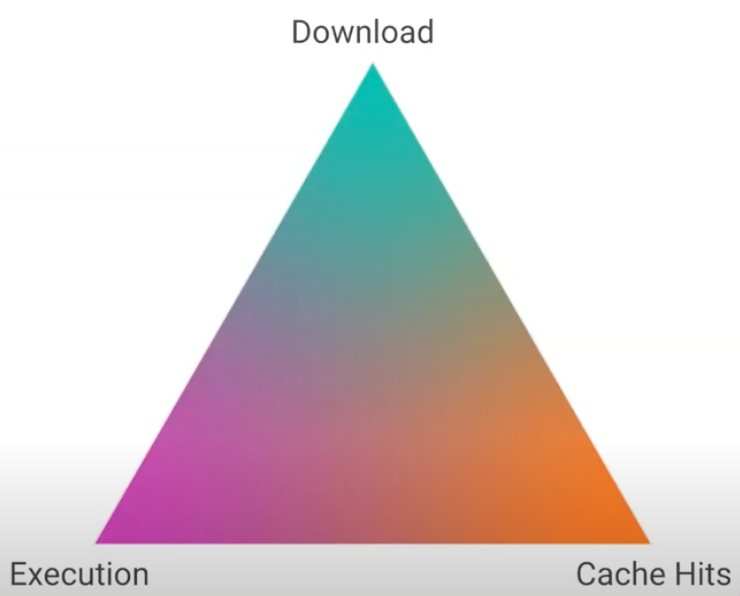

In an ideal world, the granularity and chunking strategy should aim to achieve the following goals, which are at odds with each other.

- Improve download speed: As seen in the previous sections, download speeds can be improved using compression. However, compressing one large chunk will yield a better result or smaller file size than compressing multiple small chunks with the same code.

compress(a + b) <= compress(a) + compress(b)

Limited local data suggests a 5% to 10% loss for smaller chunks. The extreme case of unbundled chunks shows a 20% increase in size. Additional IPC, I/O, and processing costs are attached to each chunk that gets shared in the case of larger chunks. The v8 engine has a 30K streaming/parsing threshold. This means that all chunks smaller than 30K will parse on the critical loading path even if it is non-critical.

For the above reasons, larger chunks may prove to be more efficient than smaller chunks for the same code for optimizing download and browser performance.

- Improve cache hits and caching efficiency: Smaller-sized chunks result in better caching efficiency, especially for apps that load JS incrementally.

-

Changes are isolated to fewer chunks with smaller chunks. If there is a code change, only the affected chunks need to be re-downloaded, and the code size corresponding to these is likely to be small. The remaining chunks can be found in the cache thus, increasing the number of cache hits.

-

With larger chunks, it is likely that a large size of code is affected and requires a re-download after code changes.

Thus, smaller chunks are desirable to utilize the caching mechanism.

- **Execute fast **- For code to execute fast, it should satisfy the following.

- All required dependencies are readily available - they have been downloaded together or are available in the cache. This would mean you should bundle all related code together as a larger chunk.

- Only the code needed by the page/route should execute. This requires that no extra code is downloaded or executed. A

commonschunk that includes common dependencies may have dependencies required by most but not all pages. De-duplication of code requires smaller independent chunks. - Long tasks on the main thread can block it for a long time. As such, these need to be broken up into smaller chunks.

Image courtesy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ImjzA7EMI6I&list=PLyspMSh4XhLP-mqulUMcaqTbLo-ZJxSX5&index=29

As indicated by the triangle above, a loading granularity that tries to optimize one of the above goals can take you away from the other goals. This is the problem of granularity trade-off

De-duplication and caching are at odds with browser performance and compression.

As a result of this trade-off, the maximum number of chunks used today by most production apps is around 10. This limit needs to be increased to support better caching and de-duplication for apps with large amounts of JavaScript.

SplitChunksPlugin and Granular chunking

A potential solution for the granularity trade-off would address the following requirements.

- Allow a larger number of chunks (40 to 100) with smaller chunk sizes for better caching and de-duplication without affecting performance.

- Address performance overhead for multiple smaller chunks due to IPC, I/O, and processing costs for many script tags.

- Address compression loss in case of multiple smaller chunks.

A potential solution that addresses these requirements is still in the works. However, Webpack v4’s SplitChunksPlugin and a granular chunking strategy can help increase the loading granularity to some extent.

Earlier versions of Webpack used the CommonsChunkPlugin for bundling common dependencies or shared modules into a single chunk. This could lead to an unnecessary increase in the download and execution times for pages that did not use these common modules. To allow for better optimization for such pages, Webpack introduced the SplitChunksPlugin in v4. Multiple split chunks are created based on defaults or configuration to prevent fetching duplicated code across various routes.

Next.js adopted the SplitChunksPlugin and implemented the following Granular Chunking strategy to generate Webpack chunks that address the granularity trade-off.

- Any sufficiently sizable third-party module (greater than 160 KB) is split into an individual chunk.

- A separate frameworks chunk is created for framework dependencies. (react, react-dom, and so on)

- As many shared chunks as needed are created. (up to 25)

- The minimum size for a chunk to be generated is changed to 20 KB.

Emitting multiple shared chunks instead of a single one minimizes the amount of unnecessary (or duplicate) code downloaded or executed on different pages. Generating independent chunks for large third-party libraries improves caching as they are unlikely to change frequently. A minimum chunk size of 20 kB ensures that compression loss is reasonably low.

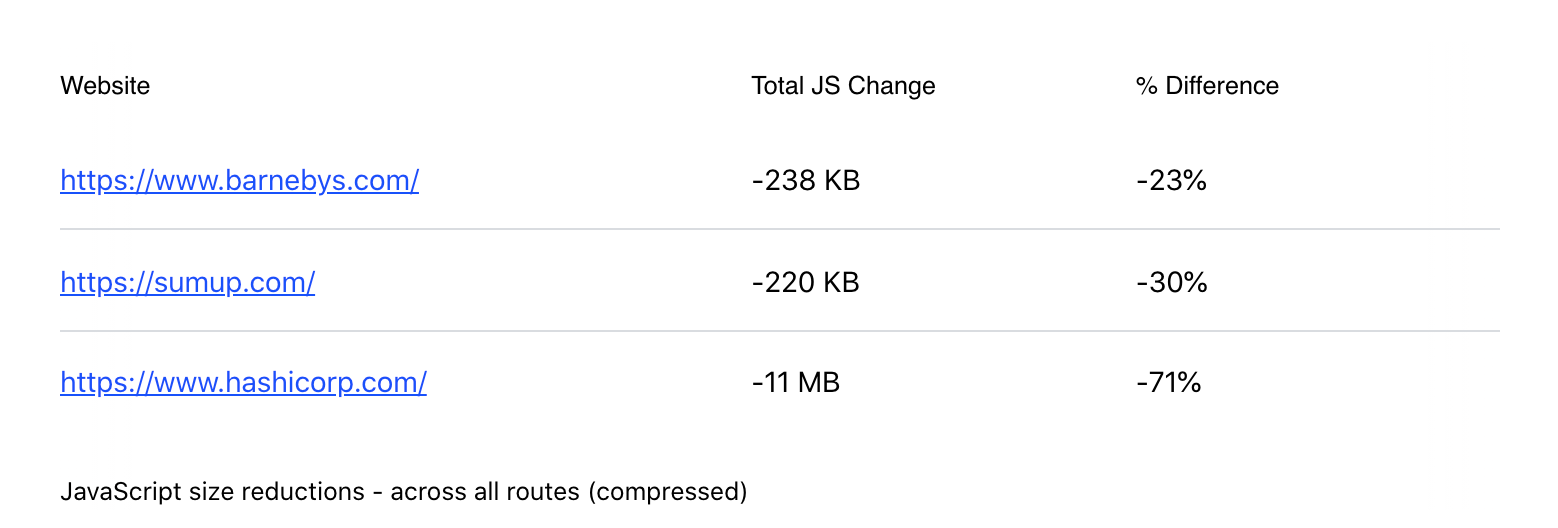

The granular chunking strategy helped several Next JS apps reduce the total JavaScript used by the site.

The granular chunking strategy was also implemented in Gatsby with similar benefits observed.

Conclusion

Compression alone cannot solve all JavaScript performance issues, but understanding how browsers and bundlers work behind the scenes can help create a better bundling strategy that will support better compression. The loading granularity problem needs to be addressed across different platforms in the ecosystem. Granular chunking may be one step in that direction, but we have a long way to go.